This is a case study into the complicated implementation of the DMCA on YouTube–what went right, what went wrong, and what can be changed for the better. The PDF is available below. The text of the paper is also available further down this page.

Additionally, below is a “poster” used at a semi-symposium to summarize the points of the paper:

1 Introduction

As of September 2019, there were more monthly users of YouTube than Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime, and Vimeo combined (Trendacosta, 2020). Nearly twenty percent of Americans watch YouTube for more than three hours a day (Trendacosta, 2020). In the U.S., YouTube has around 70% of the market share among online video platforms, and as such is the platform of choice for those looking to make money from online video creation (Chung, 2020). As of 2017, over two million U.S. creators posted on YouTube, earning about four billion dollars per year (Trendacosta, 2020). With its enormous influence, YouTube’s copyright policies not only affects its millions of creatosr, but also impact other platforms’ copyright policies (Chung, 2020).

Copyright law in the U.S. began with article 1, section 8 of the Constitution, which allows Congress to enact legislation to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8). Even though copyright has begun incorporating more modern technologies under its umbrella, the underlying goal remains the progress of science and art. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) passed in 1998 was an example of a step to theoretically update copyright law for the new millennium (Seng, 2014).

However, this was before user-generated content became popular (around 2005), meaning that the DMCA still favored mass media copyright holders and provided limited protections for users (Solomon, 2015). Since the DMCA’s policies are the basis for YouTube’s copyright policies, YouTube’s copyright policies directly in line with the DMCA also favor mass media copyright holders and provide limited protections for users. YouTube also has copyright policies that go beyond the DMCA, such as Content ID, that reinforce this bias, and the DMCA has no regulation surrounding these policies, partly because in 1998 algorithms such as Content ID would not have been easy to foresee. YouTube’s copyright policies stifle the progress of science and useful arts, directly contradictory to the original spirit of copyright, by misidentifying fair use as copyright infringement, giving users a biased and threatening pathway in order to resolve these misidentifications, and providing users limited information, creating a culture of fear in which users have to be more concerned with appeasing the algorithm and mass media copyright holders than the actual law.

2 Background on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

The Digitial Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was passed to update copyright law for the modern age, including limiting the liability of Internet intermediaries as service providers (Seng, 2014). It also serves as a template for similar defenses in the European Union, and the People’s Republic of China, and the legal foundation for YouTube’s copyright policies (although it does not prescribe all of them) (Seng, 2014). Under subsection 512(a) of the DMCA, Online Service Providers (OSPs) are not liable for users infringing copyright as long as they conform to several requirements (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998).

The relevant requirements in the DMCA for this discussion of YouTube’s copyright policies are those concerning the takedown request system and the repeat infringer system. Subsection 512(c) prescribes that the OSP will not be liable as long as they: do not have “actual knowledge” that the material is infringing, “in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent,” or when notified act “expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material” (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998). Essentially, if they are notified about copyright infringement, they must act quickly to take it down, although they are not required to seek out instances of infringement.

The DMCA goes on to describe the necessary elements of a takedown notification, including that it be a “written communication,” with a “physical or electronic signature of a person authorized to act on behalf of the owner of an exclusive right that is allegedly infringed,” an “identification of the copyrighted work claimed to have been infringed,” a statement of good faith, and a statement that the information is accurate under penalty of perjury (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998). If the alleged infringer wants to resist this takedown notification, they must provide a counter notification that has the signature of the user, their information, a statement of good faith, consent to the jurisdiction of the relevant federal district court, and identification of the material that was taken down (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998). If the claimant wants to pursue a takedown after this counter notification, they must seek a court order to restrain the user, or the OSP must place the material back online or cease disabling access to it (Seng, 2014). This is the DMCA’s described takedown process. Takedown notice, counter notification, court order.

In addition to the takedown system, in order for OSPs to be covered under the safe harbor provisions, they must also have a “policy that provides for the termination[…]of subscribers and account holders of the service provider’s system[…]who are repeat infringers” (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998). These two requirements—the takedown system and the repeat infringer system—form the basis of YouTube’s copyright policies, although YouTube’s policies are even more involved than what is required by law.

3 Content ID: Lack of Discretion

Content ID is one of the ways YouTube has gone beyond what is required of them by law, and in so doing introduced more problems into their copyright infringement policies, resulting in a bias towards large copyright holders and away from creators, resulting in the stifling of creativity on YouTube. Content ID serves as the first step in their copyright policies. Originating in 2007, Content ID is a collection of algorithms that scan uploaded YouTube videos and compares them against reference files provided by content owners (Boroughf, 2015). However, only certain righstholders are allowed to add content to the Content ID database: those who “’own a substantial body of material that is frequently uploaded by the YouTube creator community’” (Trendacosta, 2020). In practice, this means that “every major U.S. network broadcaster, movie studio, and record label” uses it, but not smaller individual creators (Boroughf, 2015). YouTube’s Content ID database has more than 25 million reference files totaling 100,000 hours of material from more than 5,000 partners (Boroughf, 2015). Content ID is responsible for around 99% of YouTube’s copyright claims, responsible for 757,993,607 claims in the first half of 2022 alone, so it is of the upmost importance to look for any flaws in it as YouTube’s first line of defense against copyright infringement (“YouTube Copyright Transparency Report”).

When Content ID finds a match, it will apply a Content ID claim to the video and either: add advertising and collect ad revenue, monitor viewership statistics, or block the video depending on the copyright owner’s Content ID settings (“How Content ID Works”). In the vast majority of cases, copyright owners will opt to monetize—in the first half of 2022, rightsholders chose to monetize over 90% of all Content ID claims (“YouTube Copyright Transparency Report”).

In theory, this policy makes sense—many copyright holders no longer view the DMCA as an effective solution to copyright protection because they must search out copyright infringement and then alert sites like YouTube, so it makes sense that they would want some review of material on YouTube in order to police copyright infringement for them (Boroughf, 2015). As of June 2022, more than 500 hours of video were uploaded to YouTube every minute, an amount that is unfeasible to have manually reviewed (Ceci, 2023). Content ID allows for copyright holders to control their copyrighted content without searching out content themselves and/or going through the arduous legal process and the normally high transaction costs associated with licensing (Boroughf, 2015). In addition, since it allows a copyright holder to track a video, it may encourage tolerated uses (Boroughf, 2015). However, in practice it allows for a few select copyright holders to block entire videos or take ad revenue from videos that fall under copyright exceptions such as fair use, those that license the material that they use, and those that were never intended to make any money in the first place without sharing any of those profits with creators regardless of the proportion of copyrighted content in the video.

YouTube itself admits that Content ID cannot distinguish “what content was properly licensed and can’t determine what qualifies for exceptions to copyright, such as fair use or fair dealing” (“Disputing a Content ID Claim”). Since videos are automatically claimed by an automated system, the copyright holders in the Content ID system (who are, keep in mind, some of the largest and most powerful copyright holders with such recognizable names as Warner Brothers) do not have to burden themselves with knowing the intricacies of fair use and attempting to argue that videos fall under fair use. They can simply sit back and enjoy the stream of income they have set up. This protects the copyright holders from liability concerning their “good faith” takedowns both because copyright claims are not takedown notices and because they are automatic—there is no good or bad faith involved.

The lack of discretion regarding fair use and licensing puts unearned money and control into the hands of large copyright holders at the expense of users. Users are entitled to their content if it falls under fair use or they have licensed the material they are using. Fair use allows for the limited use of copyrighted works for purposes such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, education, or research (“Copyright Law”). When determining whether a use falls under fair use or not, courts base their decision on factors such as: the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and the effect on the potential market for the copyrighted work (Chung, 2020). Fair use is particularly problematic for algorithms like Content ID because determining fair use requires weighing different factors to come to a conclusion in each case—discretion Content ID lacks. As a result, millions of videos are falsely claimed—in the first half of 2022 alone, over three and a half million Content ID claims were disputed, and 2,185,698 of those were resolved in favor of the uploader (“YouTube Copyright Transparency Report”). These false claims include such notable instances as Content ID blocking NASA’s mission to mars, Michelle Obama’s speech at the Democratic National Convention, and a live stream in which people were singing the “Happy Birthday” song (Boroughf, 2015). All of which were clear instances of fair use, and yet were taken down anyways. Each false claim represents possible revenue, viewers, and time lost because of an automated system that lacks discretion.

In the case of videos getting blocked or monetized, regardless of the proportion of copyrighted material contained in the video, the entire video gets blocked/monetized (Boroughf, 2015). So, even if a YouTuber has 99% original content in their video but happen to use a few seconds of a popular song, the music publisher can claim the video and reap the ad revenue, leaving the YouTuber with none—it can even put ads on a video that was not previously monetized and obtain ad revenue from a video that was never intended to make money. This is directly in contrast to the spirit of existing U.S. copyright law (although not in violation of it), as when a copyright holder seeks to obtain profits obtained by an infringer, they are “entitled to recover the actual damages suffered by him or her as a result of the infringement, and any profits of the infringer that are attributable to the infringement” (“Copyright Law”). Copyright holders are essentially entitled to the revenue that copyright infringers took from them by using their content—this is not meant to be a punitive reward. Yet, Content ID acts as a punitive reward for copyright holders, punishing users who want to use others’ content legally to create better videos (Boroughf, 2015). The punishment for legally using others’ content stifles creativity on YouTube by incentivizing users to make worse/less informative/less creative videos in order to hopefully keep the revenue/viewers from it, directly contradictory to the spirit of copyright law.

Content ID’s discretion-less claiming system not only hurts users but also hurts copyright holders who want to tolerate some uses of their content. For example, in late 2013 there was a wave of Content ID claims against video game videos, with some YouTubers reporting that up to fifteen percent of their content was now diverting ad revenues to third parties (Boroughf, 2015). This not only negatively affected the users whose videos were being claimed, but it also negatively affected game publishers. Numerous game publishers have publicly stated that they encourage game reviews and Let’s Play videos that use game footage, and yet game reviewers’ and gamers’ videos were being taken down for copyright infringement (Boroughf, 2015). This is partly because Content ID automatically claims all videos that match part of the reference file, not distinguishing between types of videos that the copyright holders may want to tolerate. In this case, while game publishers would want to claim videos that just uploaded game footage without any commentary, they did not want to claim Let’s Play videos and game reviews. However, Content ID has no way to distinguish these uses due to its lack of discretion. In this way, Content ID in fact does not encourage tolerated uses but works against tolerated uses, which once again works against creativity and creative progress on YouTube through stifling more forms of content.

Additionally, multiple rightsholders may add the same content to the Content ID database, resulting in multiple entities being able to make demands on a video, regardless of who the primary rightsholder is (Trendacosta, 2020). This is the other part of how Content ID failed both users and game publishers in 2013. In December of 2013, Ubisoft acknowledged that some of the matches may have been “’auto-matched against the music catalogue on our digital stores—it might show as being claimed by our distributor ‘idol’” (Boroughf, 2015). In this case, while Ubisoft had set it so that they were not claiming videos that used game footage, the music distributor was claiming the videos because of the game music in the background of game footage. Since Ubisoft and the music distributor are two separate entities, Ubisoft (and other similar game publishers) had to then discuss every claim with the music distributor so that they could get the music distributor to release the claim and have the videos stay up (Boroughf, 2015). In an analysis of videos taken down by Content ID claims and DMCA notices, researchers found that music claimants were 41% more likely to block gameplay videos than the average, even though overall gameplay videos are 83% less likely to be removed by a Content ID claim than an unclassified video (Gray & Suzor, 2020). These claims led to Ubisoft issuing a statement asking that YouTubers leave the video live and send them the information on the video and who flagged it so that they “’could get it cleared hopefully same day’” (Boroughf, 2015). The need for a public statement is indicative of the backlash Ubisoft was getting. Even though they had said that they tolerate uses of their content, YouTubers were still having their content claimed, leading to bad press for Ubisoft and more work for them in order to get the claims resolved. Content ID not only does not work for users because of its lack of discretion, but it also does not work for copyright holders who want to tolerate some uses of their content. Overall, it works for large copyright holders who want to passively take revenue from creators who use their content (legally or not) without being liable, and works against creators and copyright holders who want to tolerate uses, leading to stifling progress for content on YouTube.

4 Dispute System: Biased in Favor of Claimants

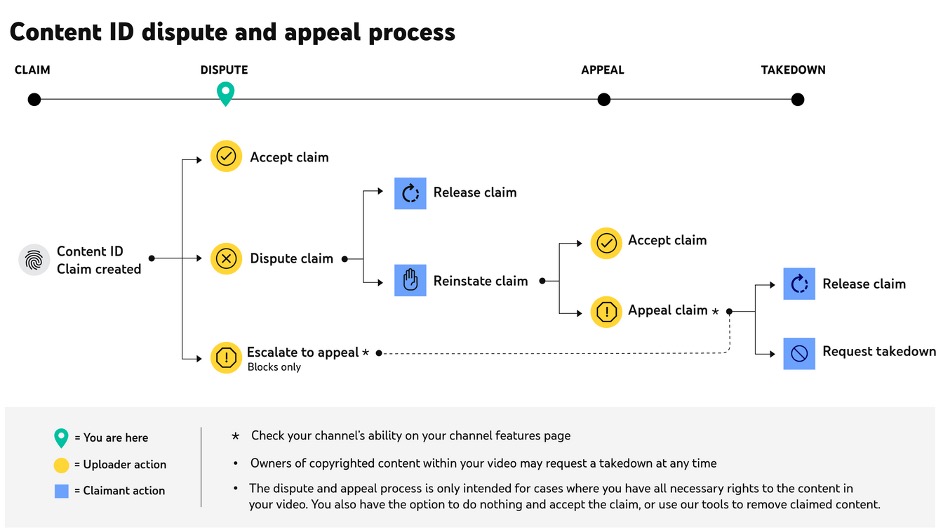

If a YouTuber gets falsely flagged due to Content ID’s lack of discretion with fair use and licensing, in order to attempt to resolve this false claim they must go through YouTube’s copyright claim dispute system. YouTube has provided a handy chart to see the general flowchart for disputes, found in Figure 1 below (“Dispute a Content ID claim”).

Content ID dispute and appeal process

A YouTuber must first dispute a Content ID claim, which YouTube notifies the copyright holder of. The copyright holder then decides if the claim is valid or not, or they let the claim expire after 30 days. If they decide the claim is invalid (upholding the claim), the creator can file for an appeal, after which the claimant again has 30 days to respond by either releasing the claim or filing a DMCA takedown request (Kaye & Gray, 2021). For videos where the Content ID claim resulted in the video being blocked, the uploader can skip the first step and begin at the appeal step to get the process resolved quicker (“Dispute a Content ID claim”). The final step—the “request takedown” option—is the only step of the process that takes place outside of YouTube, the rest are preliminary and are meant to stop the claim from escalating to a takedown request. Yet, there are flaws both in the DMCA’s takedown process, YouTube’s dispute process, and the way they are connected that creates a bias in favor of claimants.

Under the DMCA, if a counter notice is issued against a claimant who has issued a takedown request, the claimant then has a choice between accepting the counter notification or filing legal action against the infringer (Chung, 2020). The DMCA’s approach in itself is already flawed since it gives the claimants—generally larger production companies with millions to spend on lawyers—the choice between suing and letting a perceived copyright claim go. However, while the cost of litigation is not as impactful for companies like MGM or Warner Bros., it can be life or death for a small YouTuber. The 2019 report of the economic surey conducted by the American Intellectual Property Law Association found that the median cost of litigating a copyright infringement case through trial ranged from $550,000 to $6.5 million—money that most YouTubers just do not have (Chung, 2020). Even for extremely popular YouTubers such as h3h3productions, with a whopping 6.6 million subscribers, they claimed they needed to start a fundraiser to cover their litigation costs for an infringement suit in 2017—a suit they won using the fair use defense (Chung, 2020). Additionally, filing a counter notification requires the filer to reveal their contact information (Trendacosta, 2020). For YouTubers who wish to remain anonymous, this enormously disincentivizes them from fighting any takedown notices. Since the DMCA’s takedown request system ends in a potential lawsuit, YouTubers are incentivized to avoid it at all costs, and accept takedown notices even if the content they are making is fair use.

The DMCA has several main supposed safety valve provisions to prevent DMCA abuse from happening, but none provide an appealing or feasible option to creators. The first is that there is a requirement that a copyright owner submit any DMCA takedown under a “good faith belief” that they are infringing (Chung, 2020). This creates a cause of action against persons who “knowingly materially misrepresent” whether the content was infringing or taken down by mistake (Chung, 2020). However, in 2004, the ninth circuit ruled in Rossi v. Motion Picture Ass’n of America that the “good faith belief” and “knowing misrepresentation” standards required a demonstration of actual knowledge of misrepresentation on the part of a putative right holder (Chung, 2020). This is both difficult to prove for creators and requires legal action, which, as discussed above, is simply not something many creators would be able to comfortably pursue. Once again, this biases the DMCA takedown notice (and therefore the final end of YouTube’s dispute system) in favor of the claimants—generally large corporations.

Another seeming safety valve is that “a putative right holder must consider fair use before submitting a takedown request” (Chung, 2020). However, in Lenz v. Universal, the ninth circuit held that a rightsholder’s determination as to fair use passes as long as they subjectively believe it to be true (Trendacosta, 2020). This once again places an enormous burden of proof on the creators to prove active belief that the takedown request was false, and once again requires legal action. Since creators would have to prove either bad faith or belief that the request they were issuing was invalid due to fair use, this renders attaining justice for invalid DMCA claims virtually inaccessible for most creators, and so it incentivizes creators to not counter notice if they receive a DMCA takedown request and to keep the Content ID claim within YouTube’s dispute system as much as possible.

However, attaining justice within YouTube’s dispute system is also difficult. In the first two instances before a takedown request—the dispute and the appeal—the copyright holder presides over whether the dispute/appeal is valid or not (Kaye & Gray, 2021). As one YouTuber put it, “’it’s like a murderer going to court and deciding whether he is guilty or not’” (Kaye & Gray, 2021.) Copyright holders using Content ID—who are, remember, on YouTube mostly large companies—have no reason to release claims. Even if the claims are false, most YouTubers would not be able to sue them, and the fear of litigation is enough to deter YouTubers from following through on a dispute all the way to court.

Additionally, YouTube further disincentives creators to pursue claims up through takedown requests through their interpretation of the DMCA’s required “repeat infringer” policy (“Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” 1998). On YouTube, if a creator receives a takedown request (which, again, even if it is erroneous creators are incentivized not to fight), their channel will receive a “copyright strike” (Kaye & Gray, 2021). One copyright strike results in the creator going through “Copyright School,” where they must watch videos about copyright law (Kaye & Gray, 2021). In addition, copyright strikes may affect creators’ ability to monetize their videos and their access to live streaming (“Copyright strike basics”). After three copyright strikes, the user’s account is terminated, all their videos are deleted, and they are not allowed to create new channels (“Copyright strike basics”). In this way, YouTubers are further disincentivized from following through on a dispute due to the increased chance that they will get a takedown request and their income (and possibly their channel) will be in jeopardy. Additionally, copyright holders can submit a takedown request at any point in the dispute process, they do not need to wait for the dispute and appeal to be resolved (Trendacosta, 2020). So, even by disputing a claim, YouTubers are drawing the attention of massive copyright holders, who can choose to issue a takedown request at any time, resulting in a copyright strike on their channel and loss of money, and they will most likely not choose to counter notify due to fear of litigation.

Copyright holders are also able to schedule a DMCA takedown request, notifying the uploader that there will be a DMCA takedown request issued in 7 days if they do not delete the video or release the appeal (Trendacosta, 2020). This clearly threatens the user with potential litigation and provides an ultimatum for them to either release the appeal/delete the video or receive a copyright strike on their channel, which could lead to loss of revenue or account termination.

On every level, YouTubers are disincentivized from disputing Content ID claims, following through on those disputes, and going to court over those disputes. If they dispute a claim/follow up on a dispute, the claimant is presiding over it and so is more likely to say that the copyright claim was valid, and so they are then more likely to receive a copyright strike due to a takedown request being issued, which affects monetization and potentially the termination of their channel. Even if they are willing to take a copyright strike, if they counter notify, they must reveal personal information about themselves that they may not feel comfortable revealing. After the counter notification, the claimant can choose to start a legal action, which in most cases where the creator does not have access to a large amount of funds can spell financial ruin for a creator. Lastly, if they wanted to sue a company for DMCA abuse, they would both need to move through the federal legal system (since copyright law is federal) and prove bad faith or knowledge that the claim was invalid under fair use, both of which are high burdens of proof for the creator. Overall, creators are disincentivized from attempting to get retribution for false claims (which, as discussed earlier, are prevalent due to Content ID’s lack of discretion), and copyright holders can make false claims with near impunity since they do not fear legal retribution from small creators, and can make money off of content they may not be able to prove in court that they own.

5 Lack of Information

The Content ID claim and dispute process discussed above are only the way those systems work for users if they have all the information they could have access to. However, in practice, YouTubers rarely have all the information, and there are many common misconceptions with regard to concepts such as fair use that lead to the claim and dispute system working even worse for content creators than it already does.

For instance, YouTube says that due to “’agreements with certain music copyright owners[…]this may mean the Content ID appeals and counter notification processes won’t be available’” (Kaye & Gray, 2021). YouTube has shared no information about which copyright owners this applies to, and so creators may find themselves blindsided by not being able to appeal Content ID claims. Additionally, sometimes claimants can be difficult to contact, and YouTube does not give much help—this resulted in one YouTuber being unable to locate the claimant, saying “’How am I supposed to resolve the issue with the claimant when there’s no way to contact the claimant?’” (Kaye & Gray, 2021).

Additionally, trade secret laws often prevent public access to automated private regulatory systems such as Content ID (Gray & Suzor, 2020). In order to find information about how Content ID works, creators mostly turn to “educated guesses made from experiencing the system first hand” (Trendacosta, 2020). This results in creators speculating about what will trigger the Content ID algorithm. In a study of 144 YouTube videos in which creators discuss YouTube’s copyright policies, creators often speculated about this, with some thinking it would only claim copyrighted material over 20 seconds long, and others arguing that it could be triggered by much smaller amounts (Kaye & Gray, 2021). In favor of the latter theory, in one instance a ten-hour video of white noise had less than a second claimed by a rightsholder (Trendacosta, 2020). Additionally, some YouTubers in the study warned that YouTube’s royalty free music library was untrustworthy, that the license could be revoked at any time, resulting in a video being claimed (Kaye & Gray, 2021). Since a Content ID claim, even an invalid one, will result in loss of revenue and views, creators are constantly trying to figure out the “rules” that they can abide by in order to stave off Content ID, yet there are no clear rules, resulting in a “’culture of fear’” as one YouTuber put it (Trendacosta, 2020).

Due to the lack of clear rules from YouTube on what will get through Content ID and lack of information on fair use, YouTubers are essentially forced to become copyright experts if they want to be able to defend their use of copyrighted content. Creators must attempt to figure out what exactly constitutes fair use and what will result in them being sued—an example of this is the multitude of “fair use misconceptions” articles, which list things common on YouTube that technically are not fair use, such as giving credit in the description, the channel not making money, and making covers of songs (McDuff, 2015). It is easy to understand why creators would think this would protect them, as many videos using copyrighted content such as tv show edits can be left up since the Content ID copyright holder can choose to take no action on claims, and then creators are blindsided when, using the same tactics, their videos using other copyrighted material are claimed and their appeals are unsuccessful (Trendacosta, 2020). This contributes to the “’culture of fear’” as no one is exactly sure how it works, and the distinctions between Content ID copyright holders leads to uneven enforcement of copyright, increasing the doubt around what policies truly are even more.

Even when some YouTubers may feel that they have finally figured out Content ID’s rules, they may completely change on them. The Content ID filter changes constantly, so videos that once passed constantly need to be re-edited (Trendacosta, 2020). Todd Nathanson, who runs the YouTube account “Todd in the Shadows,” with over 300,000 subscribers, said that he can tell when there has been a major change to Content ID because hundreds of videos that had previously passed are suddenly flagged (Trendacosta, 2020). For Lindsay Ellis, a creator with millions of subscribers, after a major change to the Content ID system it took three weeks to deal with the new claims that came in (Trendacosta, 2020). In order to get these videos reinstated, creators either have to re-edit videos until they pass Content ID or go through the thoroughly flawed dispute process, which can take time. Internet publishing is time sensitive, and “an ill-timed block can severely impact views and, therefore, revenue,” therefore creators are incentivized to attempt to pass Content ID (Trendacosta, 2020). However, attempting to re-edit the video can be extremely frustrating, as Harry Brewis, who runs the YouTube channel “hbomberguy” found in July 2020 when he uploaded a video criticizing the animated series RWBY. In order to get past Content ID, he repeatedly edited and uploaded the video, and he said that “[t]he shocking part was every time it happened I thought, ‘Oh that’s great, it only got hit twice, that’s really encouraging’ and then the next one would get hit three times’” (Trendacosta, 2020). The infuriating nature of editing videos to get around Content ID is directly attributable to the lack of information available to YouTubers as to what will get through the filter and the filter constantly changing.

Constantly reinforcing the culture of fear is the way YouTube presents the dispute process. In most of the YouTube help pages concerning the dispute process, it will contain a sentence to the effect of “This decision shouldn’t be taken lightly. Sometimes, you may need to carry that dispute through the appeal and DMCA counter notification process” (“Frequently asked questions about fair use”). YouTube also commonly warns creators that disputing matches can result in a strike, and, if enough strikes accumulate, the loss of their channel (Trendacosta, 2020). While this may seem like YouTube is simply informing creators of the risks, through this continual emphasis on the perils of disputing a claim while not emphasizing that it could result in them getting their revenue back or the video being put back incentivizes creators to accept invalid claims by invoking the fear of litigation and/or channel termination. For instance, when Lindsay Ellis first began disputing Content ID claims, she says, “[I was] scared to do it because of the way YouTube wants you to think it works. Like, ‘are you sure you want to do this? You could lose your channel’” (Trendacosta, 2020). This results in revenue going to copyright holders that YouTube works closely with, keeping YouTube’s relationships with them positive, which is good for YouTube.

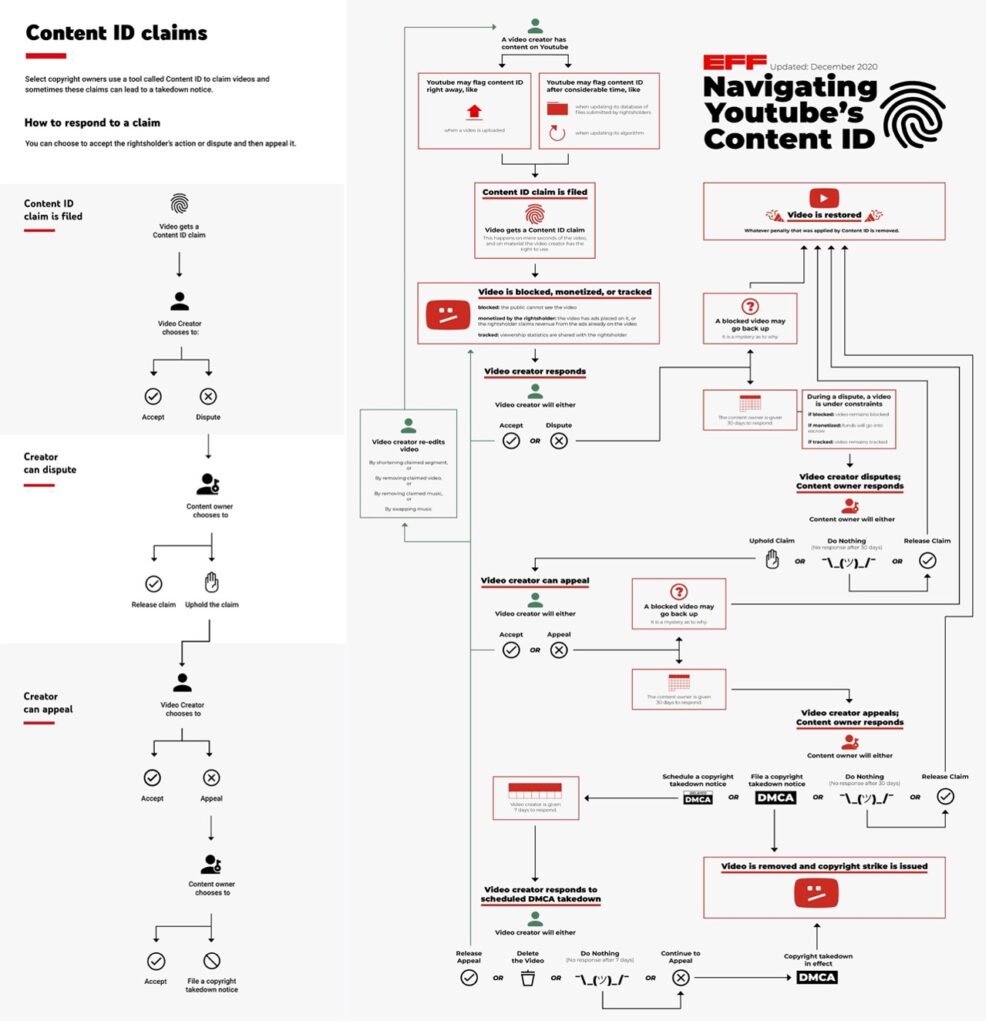

In addition to YouTube emphasizing the potential for channel termination/litigation, the user interface also constantly changes and presents problems for creators. During an interview with Lindsay Ellis and her producer Elisa Hansen, they found that the interface had changed since they last used it and they “could not even navigate to see how many Content ID claims Ellis’ channel had” (Trendacosta, 2020). Additionally, the interface has not provided enough information about the dispute process. Ellis’s account “sat with hundreds of Content ID claims for years because they did not know they could contest them” (Trendacosta, 2020). The dispute process is confusing and uninformative for creators, especially for those not well versed in YouTube. In January 2020, NYU Law School posted a video where they used portions of songs to discuss how experts analyze songs for similarity in cases of copyright infringement, which was flagged by Content ID. While those working in intellectual property law at NYU Law were certain the video did not infringe, they ended up “lost in the process of disputing and appealing Content ID matches[…]They could not figure out whether or not challenging Content ID to the end and losing would result in the channel being deleted” (Trendacosta, 2020). As an example of how the simple-looking dispute pathway in Figure 1 does not accurately represent how confusing the actual process can seem, the Electronic Frontier Foundation created a side-by-side comparison of YouTube’s given pathway with how the Content ID dispute system actually works, found in Figure 2 below (Trendacosta, 2020).

EFF Diagram of Navigating YouTube’s Content ID

This illustrates how confusing it is for creators—especially those new to YouTube or not technologically savvy—to navigate Content ID and know how to keep themselves safe from copyright strikes, channel termination, and ultimately litigation. The lack of information available to users about Content ID, and the obfuscation of the dispute process in the user interface and help pages results in creators not disputing their claims because they are uninformed and fearful of what may happen to them and their channel.

6 Policy Implications

A. CASE Act

The Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act was passed in December of 2020, and is meant to help lower the costs of litigation of takedown requests (Henris, 2021). This would lessen the effect of threats of litigation and therefore lessen the potential threat that disputing a copyright claim poses to users. It sets up a small claims court, in which claims will be heard by a Copyright Claims Board made up of 3 full-time copyright claims officers (Henri, 2021). The board will be able to hear copyright infringement claims, actions for a declaration of noninfringement (such as a declaration of fair use), claims that a party knowingly sent false takedown notices, and related counterclaims (Henri, 20210. An attorney is not essential (lowering costs of litigation significantly) and proceedings do not require in-person appearances by parties (Henri, 2021). This looks to be a promising reform to lessen the financial threat of litigation.

Since the Copyright Claims Board only started accepting claims in June of 2022 and has not made its first decision, its efficacy cannot be determined (Mentzer & Keegan, 2022). Of the claims in the first two weeks of the Board going live, most of the claims are for the alleged infringement of photographs (Mentzer & Keegan, 2022). This may mean that YouTubers may not fully take advantage of this path, or that litigation is still too ominous for many, although it is difficult to make any determination in such early days. One major concern with the CASE Act was that either party is able to opt out of the small claims court, causing the dispute to be handled as normal. This was a concern since large companies with large amounts of money at their disposal could decide to opt out and pursue normal litigation, which would be much more intimidating for users. As of January 2023, almost 300 cases had been filed, and only 20 claims had ended with the respondents opting out of the Board’s jurisdiction, which is a positive sign for the Board (Setty, 2023). However, it is still too early to say whether the CASE Act will be effective or not.

B. Proportional Monetization/Blocking

A major concern discussed in section III is that Content ID claims block or monetize all of a video regardless of the proportion of copyrighted material contained therein. In order to help fix this, policy could change so that claimants can only claim revenue proportional to the amount of copyrighted material and can only block the portion of the video that is copyrighted material. While YouTube has little incentive to implement this, it could be changed by amending the DMCA to ensure that any monetization/blocking of videos will be proportional to the amount of copyrighted material in it (Solomon, 2015). While this would not eliminate the incentive for large copyright owners to place invalid Content ID claims, it would both mitigate the incentive for large copyright owners to abuse the DMCA/YouTube’s copyright claim dispute system and would mitigate the risk for creators to put clips into their videos. This would help protect fair use, something Content ID currently puts in peril, by ensuring that creators still get revenue from their original content.

C. Education for Creators

As discussed in section V, creators have little information on how exactly the Content ID/dispute system works. This could be fixed by amending the DMCA to add a provision that requires providers to educate content creators on their rights under the fair use doctrine as well as platform-specific policies (such as Content ID) (Solomon, 2015). Additionally, creators have mentioned a need for a dedicated helpline “with a human being on the other end” being needed (Trendacosta, 2020). This may not be feasible for smaller platforms, but the DMCA could have an amendment that requires platforms above a certain size to have a helpline.

Depending on how much traffic this helpline would get, it may require significant manpower, and so figuring out the size cutoff may take some revisions. However, this would help with the lack of information YouTubers currently have about how their videos can get through Content ID and how the dispute process works.

D. Penalize Copyright Holders for False Flags

Some have proposed penalizing copyright holders when their flags turn out to be invalid (Solomon, 2015). However, this poses a problem. Content ID is automatic, and so any false claims would not be necessarily the fault of the copyright holders but of the algorithmic system. This could be amended to copyright holders getting penalized for dismissing valid disputes, although as discussed previously, creators are incentivized not to dispute, or to accept dismissed disputes as to avoid litigation or channel termination, and so invalid disputes may not get resolved correctly. In this way, while well-meaning, this proposed solution may have little impact on the efficacy of YouTube’s copyright policies.

E. Oversight of Disputes

The lack of oversight over disputes and counter notifications poses a problem for the impartiality of the decisions. For counter notifications, the DMCA could be changed to state that it will be presided over by a third party. However, who this third party is poses an issue. If it is a YouTube representative, then they may still be biased towards large corporations that they have relationships with. If it is a judge/lawyer/intellectual property expert, this may result in extra costs that would further deter creators from seeking justice.

For disputes, these are not required by the DMCA and so are up to YouTube to decide how to run. In order to encourage impartiality in these decisions, some have suggested that a third-party website should be required to be set up similar to ChillingEffects.org (Boroughf, 2015). Blocking requests and monetization requests would be sent to the website along with information on who the claimant is, why the video is blocked/monetized, and any other information necessary to explain the story (Boroughf, 2015). The public would also be allowed to comment on a block/monetization, which would increase public pressure on claimants who make invalid claims (Boroughf, 2015). It would also provide more information on what exactly gets claimed by Content ID, who the main claimants are, and what types of claims get resolved in different ways (Boroughf, 2015).

7 Conclusion

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act was a meaningful step towards bringing copyright law into the new millennium through protecting OSPs from being liable for user-uploaded copyright infringement. However, due to its bias towards copyright holders and its lack of regulation as to what sites such as YouTube could do to police copyright, it resulted in YouTube being able to create copyright policies that hurt millions of users and give unearned money to large copyright holders. Content ID’s lack of discretion leads to legal uses of copyrighted material being blocked or monetized in favor of the rightsholder. The dispute system biased towards claimants and ending in potential channel termination and/or litigation discourages creators from disputing invalid claims. On top of this, the lack of concrete information and advice for creators as to what gets flagged by Content ID and how to dispute claims prevents those who may want to dispute claims from doing so and creates a culture of fear. By providing more information, oversight, proportional monetization/blocking, and a lessened cost of litigation, copyright law may be able to more effectively protect content creators in the new millennium, not just copyright holders and platforms. The DMCA could then fall more in line with the goal of copyright law in general, promoting creativity and the progress of science and the arts.

8 References

Boroughf, B. (2015). The next great YouTube: improving content ID to Foster creativity, cooperation, and fair compensation. Alb. LJ Sci. & Tech., 25, 95.

Ceci, L. (2023, January 9). Hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/259477/hours-of-video-uploaded-to-youtube-every-minute/#statisticContainer

Chung, T. S. (2020). Fair Use Quotation Licenses: Private Sector Solution to DMCA Takedown Abuse on YouTube. Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, 44(1), 69-92.

Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17), S. 94-553. https://www.copyright.gov/title17/title17.pdf

Copyright strike basics. (n.d.). YouTube Help. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2814000

Dispute a Content ID claim. (n.d.). YouTube Help. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797454

Frequently asked questions about fair use. (n.d.). YouTube Help. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/6396261?hl=en#zippy=%2Chow-does-fair-use-work%2Cwhat-constitutes-fair-use%2Cwhen-does-fair-use-apply%2Chow-does-content-id-work-with-fair-use

Gray, J. E., & Suzor, N. P. (2020). Playing with machines: Using machine learning to understand automated copyright enforcement at scale. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 2053951720919963.

Henris, C. (2021). Oof! nice try congress the downfalls case act and why we should be looking to our cousins across the pond for guidance in updating our new small claims intellectual property court. Journal of Intellectual Property Law, 29(1), 175-208.

How Content ID Works. (n.d.). YouTube Help. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370?hl=en

Kaye, D. B. V., & Gray, J. E. (2021). Copyright gossip: Exploring copyright opinions, theories, and strategies on YouTube. Social Media+ Society, 7(3), 20563051211036940.

McDuff, R. (2015, August 12). Debunking (YouTube) Copyright Myths. Medium. https://medium.com/the-video-creators/debunking-youtube-copyright-myths-4571df5a5bf7

Mentzer, S., & Keegan, T. (2022, July 6). The Copyright Claims Board goes live: early trends. White & Case. https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/copyright-claims-board-goes-live-early-trends

Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration. (1998, October 27). Public Law 105 – 304 – Digital Millennium Copyright Act. [Government]. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-105publ304

Seng, D. (2014). The State of the Discordant Union: An Empirical Analysis of DMCA Takedown Notices. Virginia Journal of Law & Technology, 18(3), 369-473.

Setty, R. (2023, January 13). New Copyright Venue Fields Hundreds of Claims, Evoking Optimism. Bloomberg Law. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/new-copyright-venue-fields-hundreds-of-claims-evoking-optimism

Solomon, L. (2015). Fair users or content abusers: The automatic flagging of non-infringing videos by content id on youtube. Hofstra L. Rev., 44, 237.

Trendacosta, K. (2020, December 10). Unfiltered: How YouTube’s Content ID Discourages Fair Use and Dictates What We See Online. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/wp/unfiltered-how-youtubes-content-id-discourages-fair-use-and-dictates-what-we-see-online

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8.

YouTube Copyright Transparency Report H12 2022. (2022). https://storage.googleapis.com/transparencyreport/report-downloads/pdf-report-22_2022-1-1_2022-6-30_en_v1.pdf